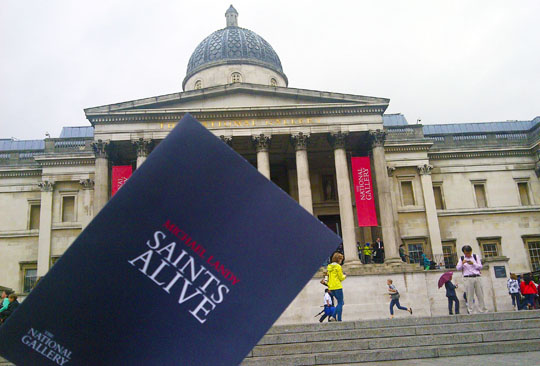

Michael Landy- Saints Alive @ The National Gallery

Little Max and God. The first time I heard about God I was five years old. It was early morning and my great nanny Lisa and I were walking to a nearby field to look for lost sheep (I promise this is not Christ/shepherd analogy). I quizzed Lisa why sheep want to run away and she replied- “Ask our Holy Father in heavens, He will always hear you out”. Having been born in Communist Russia, I never heard such an advice before and got immensely intrigued. Later that day, as Lisa was dosing on the grass near the found sheep, I cocked my head up and asked the wispy clouds in the glorious blue sky, what I thought was, a series of pretty searching questions. There came no answer, but from looking at the sky for a long time I felt like I was falling into a bottomless azure pit. That was the beginning of my vertigo and the end to my god-searching.

Violence into sainthood. Saints Alive at The National Gallery is also a kind of god-searching, or rather searching to understand the mechanics of faith- which to some comes so easily, to others- less so. So this isn’t Barocci’s saints I wrote about in an earlier blog. Michael Landy’s latest installation definitely doesn’t dwell on their divine destiny. Instead he focuses on the juicy and graphic violence, you know the kind that gets you canonised. There’s the stigmatisation of St Francis and St Gerome’s flagellation; here’s St Catherine being broken on a wheel; there’s St Thomas poking Christ’s wounds; over here St Appolonia pulling out her own teeth, one by one…

As Landy’s a self-proclaimed philistine in art history, the whole point of the exhibition, it seemed, was to offer a refreshing perspective on art. The perspective is certainly refreshing and startling, and even freaky. It also manages, predictably, to rattle a few cages- e.g. Brian Sewell, who, as per his contributions in ES, doesn’t seem to like much that comes out of TNG these days.

You make them hurt them. Notwithstanding Mr Sewell’s efforts, at the time when I went there on a Saturday morning, it had a healthy queue at the entrance. The larger-than-life automaton of St Apollonia that you could see through the double doors was a good indicator of what was to be expected inside- at a press of a floor pedal the statue motioned to pull its own teeth with a pair of oversized pliers and in the process chipped away at its angelic face. The rest of the fibreglass-plaster-and-paint kinetic statues re-enacted self-harm at my command on a biblical scale.

Even though by the time of my own visit two of the statues broke down, it didn’t diminish the effect of the rest of the exhibits. In the almost religious silence of the National Gallery the sudden violent animation of St Thomas’ disembodied hand repeatedly prodding Christ’s torso made for creepy experience, which in a weird way brought home the violence and pain of Jesus’ martyrdom.

In art symbolism is all. Here it turns round and hits you in the face, almost. I suppose the next step would be to extend the interaction with the display by actually flagellating, stigmatising and breaking us the visitors on Catherine’s wheel. Though some people might actually enjoy that…

If there is a message, it is subversive. Whilst inviting you to turn St Catherine’s Wheel in the re-enactment of how she was tortured for her Christian believes, you can read on the same wheel her life in a neat, yet seditious, resume. In homage to St Francis’ refusal of earthly delights, his statue becomes a lucky dip arcade machine, bestowing on visitors free t-shirts. The automaton next door hits itself in the face with a Crucifix- after you deposit money in its coin slot. There doesn’t seem to be much of an outcry from the religious contingent. I’m guessing this is mainly because most people are not familiar with the imagery altogether or just don’t care?

In my earlier post I mentioned Barocci, who spent his life contemplating and depicting religion, which he was so obsessed with. For him The Holy Family was as real as his own parents, his painful wasting disease- the first step towards martyrdom. And so his paintings inspired in others an even greater devotion. Today, when the Sunday School is less popular that even a few decades ago, I’m guessing, most gallery visitors can’t distinguish between Mary Magdalene and Virgin Mary. It might well have to be something as interactive and unsubtle as an automaton plunging a cleaver into its own temple to bring the myths of these saints from relative obscurity and to the forefront of our attention.